Fishers’ Tales is an arts-based storytelling project that collects the wondrous tales that fishers enjoy telling about their ocean adventures. Each story is accompanied by a unique artwork. You can find out more about the artists here.

The project hopes to build both awareness and solidarity with subsistence and small-scale fishers, who have enormous knowledge and care for the ocean that sustains them. Fishers story, their observations and the meaning that the ocean holds for them has a lot to offer ocean governance in South Africa and should be an important part of decision-making processes.

The project contributes towards a bigger One Ocean Hub project for inclusive and transformative approaches to ocean governance. The project is managed by the Urban Futures Centre of the Durban University of Technology in partnership with the South Durban Community Environmental Alliance (SDCEA). It is funded through the Deep Emotional Engagement Programme (DEEP) Fund (administered by the One Ocean Hub).

Thomas’ story on indigenous fishing

This artwork and accompanying story illustrate the inter-linkages between small-scale fishers’ human rights to livelihoods, food and culture and inter-generational transmission of Indigenous knowledge , which is protected as part of the right to culture, and also as part of children’s human right to education. In addition, this artwork and story reflect on the tensions between customary and modern approaches to fishing, the role of governments in preventing over-fishing, and the importance of ocean protection from small-scale fishers’ perspective.

Nibela River, Kenneth Shandu, Oil on canvas, 2021

Thomas’ story: I learned how to fish from my uncles who used to go fishing since I was a kid. My uncles used to knit the nets and fish every day, and they would bring bulks of fish home. I realised that fishing is important as my uncles brought food for all of us to eat and that is what caught my attention. Then I started to follow them when they were going fishing. I started to seriously join them in 1998, and since that time I have learned to fish independently. The independence grew in me. I have realised that to be a man you must work hard to survive, and for me, I had to be brave by going into the water to fish. Fishing has been part of the culture in the area, KwaNibela has become a fishing village because everyone from kids, adults, fathers, old people, and even mothers you see them pulling up their skirts and jump in the water to fish. Read more >>

Roy’s story by Doung Jahangeer: ‘The sea is my farm’

This artwork and story illustrate the complexity of small-scale fishers’ livelihoods and the ways in which national regulation may not be suitable to ensure the protection of small-scale fishers’ economic and social human rights.

Doung Jahangeer, photograph, 2019

Doung Jahangeer, photograph, 2019

Roy’s story: In September 2019 my family and I went on holiday with some friends to a small costal town called Umzumbe approximately 100 kilometres south of Durban. When we arrived we all clambered down the dune path to get our feet into the cool sand. There the sea was calm and the sun was gentle. In the distance I noticed two fishers fishing on the rocks. Since I have often been curious about subsistence fishers and was feeling bold under the expansive blue sky I decided to go talk to them. “Did you catch anything” I asked. “It’s not biting yet” replied one of the fisherman. This is when I met Roy Nhlumayo. A man of the sea with a rugged face beaten by years of being in the sun and the wind, Roy was nevertheless in his element: “The sea is my farm.” Read more >>

Layla’s story: In a perfect world, fishing has no gender

This artwork and story illustrate gender dynamics within the small-scale and recreational fisheries sectors. It serves to reflect on women’s human rights in the fisheries context.

Lina Macanhe, photograph, 2021

Lina Macanhe, photograph, 2021

Layla’s story by Thabisile Gumede: The fishing industry is often viewed as a male-dominated space, and in many ways it is. However, this does not deter women fisher folk like Layla from making her mark when she takes her rod and casts it out on the North pier.

In a perfect world, men and women fisher folk would get along and focus on the task of fishing without any qualms. This is far from reality as Layla has to regularly put out proverbial fires between men and women fisher folk who have trivial arguments. In a heated argument with one of the men on the North pier whilst fishing, she was told to “shut your mouth” and “don’t act like a man here. You want to act like men and catch fish”. These words were spoken following a minor altercation where fishing lines got tangled just because the man saw that she caught two shad in quick succession. Read more >>

Riaz’s story: a violation of the sea

This artwork and accompanying story illustrate the competition between large-scale and small-scale fisheries, and the negative impacts on the human rights of small-scale fishers of dwindling fish stocks.

Ezami Molefe, photograph, 2021

Riaz’s story: There’s a major difference between a person that is fishing with a rod and reel and a person who’s fishing off the boat, because a person with a rod and reel is fighting a fish. It’s a tug of war, and you have come into no mans’ territory because a fish has got power in the water, plenty, no matter your size. And if you catch four fish you are tired. I promise you, your arms are sore, your muscles are aching, your feet are shaking and that’s what happens to any fisher out there. So, if you’ve got four, you’ve done brilliant but then you are so buggered. But with the trawlers out there they put out a net, and you know it’s the wrong term and I’ve been told one too many times not to use this terminology, they are raping the sea. But there’s no other way to put it because they are taking everything from like guppy to monstrous sizes. They’re taking it all and they’re not thinking about what they’re taking out the sea. Read more >>

Tozi’s story: Fishers unite

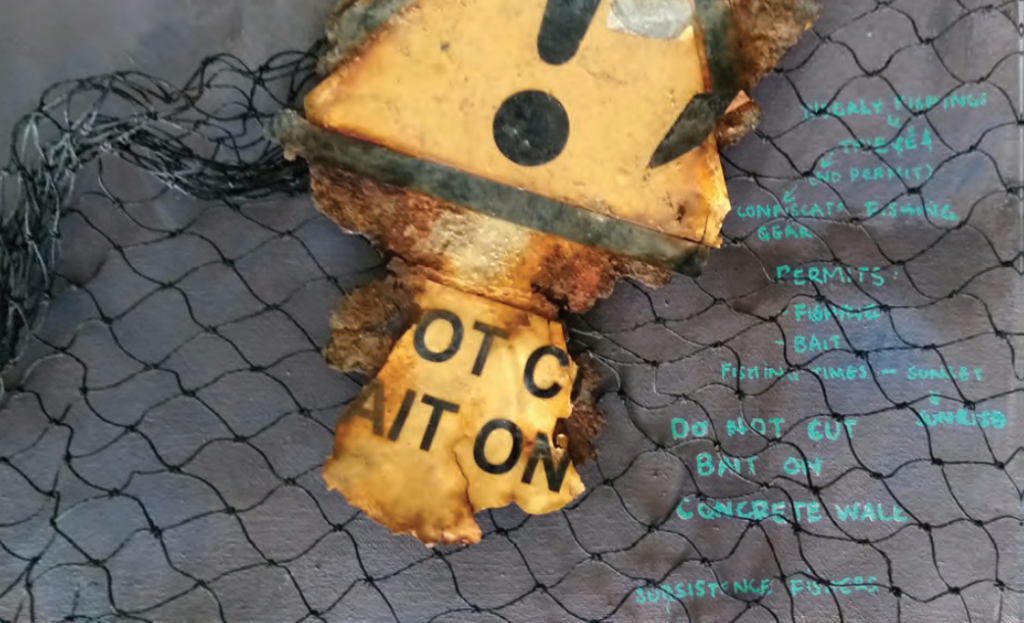

This artwork and accompanying story illustrate the mobilization of small-scale fishers to protect their human rights, including their political and civil rights and their right to be protected from racial and other forms of discrimination. The story also speak about small-scale fishers’ human right of access to justice, the misalignment between national regulation and the negative human rights impacts that can arise from conservation activities and enforcement.

Rohini Amratlal, section from Risks, 2021 (Found objects)

Tozi’s story: My name is Tozi Mthiyane from uMgababa, (South coast of KwaZulu Natal), I reside under Chief Filbert Luthuli. I started to get serious about fishing in 2012 and I was taught by David Shezi who even introduced me to the Masifundise program. If I remember it was March where Mr. Masinga from Masifundise came to uMgababa to gather fishers under Masifundise and that is where I started to get serious about fishing and I never looked back. There is nothing else that I do to earn money for a living besides fishing. My whole existence depends on fishing, fishing is the only thing that I know and love the most. Masifundise played a big role because they taught us about our rights and to fight for them as fishers because we were discriminated and we were not allowed to fish anywhere at sea. Read more >>

Layla’s story: A family that fishes together, stays together

This artwork and accompanying story illustrate the inter-generational transmission of Indigenous knowledge which is protected as part of the right to culture, and also as part of children’s human right to education.

Nompilo Mthethwa, photograph, 2021

Nompilo Mthethwa, photograph, 2021

Layla’s story by Thabisile Gumede: Spending time together is one of the greatest gifts families can give to one another. Not only does quality time strengthen and build family bonds, but it also provides a sense of belonging for everyone in the family. Add fishing to the mix and you have a winning formula. At least that is Layla’s viewpoint on the matter.

Known affectionately as ‘Aunty Layla’ to the fisherfolk, she has managed to become a successful subsistence fisher for the past 28 years whilst nurturing a strong family unit alongside her husband Bob, who has been reeling in fish for the past 35 years. With her husband as her astute yet affectionate teacher, Layla learnt how to fish with hand lines in the Bay of Plenty where she tried her hand at catching small fish before advancing to the bigger fish. Once she had mastered her technique, she was ready for fishing at the beach. Read more >>

Tamlynn’s story: A dwindling species

This artwork and accompanying story illustrate small-scale fishers’ environmental concerns, including ocean plastics among many other threats, such as deep-seabed mining, over-fishing, and pollution. All these threats are exacerbated by climate change and threaten small-scale fishers’ human rights to food.

Zimvo Nonjola, photograph, 2021

Tamlynn’s story: I don’t have much hope of what the ocean’s going to be like. I feel emotional even with that question. I mean the ocean is pretty messed up. Even in our last couple of years we can see the fishing is not the same as it used to be. More often than not you sit and you catch absolutely nothing, or just strange species. I mean we went to Zini beach, the last time we did beach fishing, all we caught were these small goblin sharks. It’s like the ocean is just filled with sharks now. They’re the only things that can maybe survive these hostile conditions that the fish are living in. At Zini all you’re catching are eels and crabs and small tiger fish. It’s not good. So obviously we have a hundred hopes you know, all the things that we do against the deep-sea mining, now these power ships, the plastic pollution, sewage that’s being pumped; I mean we’re trying our best at every turn to try and make some sort of difference, but I don’t know where it’s going. I don’t know if it’s enough. Read more >>

Mr. Mbhele’s story: The oppressed fisherman

This artwork and accompanying story illustrate historic discrimination of small-scale fishers, as well as current misalignment between national regulation on small-scale fisheries and small-scale fishers’ human rights to food and livelihoods.

Net fishers, Kenneth Shandu, oil on canvas, 2021

An ocean full of fish is any fisher’s dream. At the peak of Apartheid, a black man could barely stand on the ocean shore line let alone fish. A fisher was not attacked for fishing without a permit, but for the colour of their skin and for being in a whites-only designated area. “We were just thieves, we became thieves. We just became poachers, so whenever those khaki wearing guys came along, then you’ve got to run into the bushes,” Mr. Mbhele recalls. Their fishing gear was brutally taken and the black fisher had no rights to claim it back. It was not easy being a black fisher in that era. Mr. Mbhele once had an encounter with a group of men that came to fish in Durban from the Orange Free State, now known as the Free State province. They were burly looking rich folk who had an air of arrogance and pride. “When you fish amongst them, once your fishing line crosses theirs, they pull out their cigarettes and then they burn it off. You’ve got nothing to say. You start talking, they beat you up,” shares Mr. Mbhele. Read more >>

John Peters’ story: Segregated

This artwork and accompanying story illustrate historical and present forms of racial discrimination against small-scale fishers, and their knock-on negative impacts on small-scale fishers’ human rights to food and livelihoods.

Privilege in the distance, Rohini Amratlal, watercolour on Fabriano, 2021

Privilege in the distance, Rohini Amratlal, watercolour on Fabriano, 2021

John Peter’s story: So, like growing up in Apartheid times, did you face any kind of opposition? Lots of it. We really tried to keep away from hot spots where racism was rife. Two popular shad fishing spots were at Toti Rocks, Amanzimtoti and Winkelspruit, and you know, we were just like segregated on those rocks. Whites there, Indians here, and yet the Whites were like privileged to flick the line a short distance and catch the fish, but we had to fish closer to the shore. On the rocks, but closer to the shore. These guys were privileged to stay at the front and throw out in the deep and catch their fish. Read more >>

Mr. Mbhele’s story: a fishing heritage in peril

This artwork and accompanying story illustrate the inter-generational transmission of Indigenous knowledge which is protected as part of the right to food, livelihoods and culture, and also as part of children’s human right to education. The story also reflects on the multiple threats to ocean health, and the threats to small-scale fishers’ human rights deriving from decisions on offshore oil and gas development, mining, ocean plastics, and their implications for future generations.

Ezami Molefe, photograph, 2021

Mr. Mbhele’s story by Thabisile Gumede: When other thirteen-year-olds were out playing with their peers, Mr. Mbhele was honing his skills as a young fisherman whilst he accompanied his father who was a fisherman. He would go fishing for shad and salmon and then he used to invite him at night for crab fishing. “I used to carry the lantern for him and put the lantern over the water where there was a rocky place. And then he would come and spear them, and peel them off and put them in a bag, and in the morning, I would go and sell them at the Marina Beach Hotel in those days. It’s no more there now, that hotel” Mr. Mbhele reminisces. Passing on the fishing baton to instill a sense of identity and culture in his children, Mr. Mbhele has taught his children how to fish so that they could decide if fishing was a viable career path for them. Read more>>

Thabisile’s story: The battle for the piers

This artwork and accompanying story illustrate how lack of access to fishing grounds negatively impacts on small-scale fishers’ right to food, and the importance of small-scale fisher’s civil and political rights.

Nompilo Mtethwa, photograph, 2021

Story by Thabisile Gumede: Fishing from a pier is one of the best experiences a fisher can have. But the experience can be marred when the fisher has to contend with political issues of access to deep-water piers. Without access to these piers, Durban subsistence fishers have had to frequently engage in peaceful protests in a bid to gain access to the new pier at the beachfront. Their protests and meetings with the eThekwini Municipality have been to no avail as the pier remains closed off to the fisher folk, but open to the public who walk their dogs, cycle and skate. Piers range greatly in height and length, depending on where you are and the tide. On the current pier that the fisher folk have access to, when the tide is out there is no water around the pier, but sand. When the tide is in, the water bashes over the pier thereby drenching them to the bone. At times it washes out belongings into the sea which is a loss to them. A lot of their tackle, bags, clothes and even bait gets washed off the pier, whereas on the deep-water pier, when the tide goes out; the water doesn’t go right out. Subsistence fishers claim that the piers are rightfully theirs as they were using them before they were renovated, but they were never handed back to fisher folk. Read more >>

Andre and William’s story: You live by the sea, you die by the sea

This artwork and accompanying story illustrate the deep connections between small-scale fishers and the ocean, which serve to understanding their cultural and social rights.

Brotherhood, Kenneth Shandu, oil on canvas, 2021

Andre and William’s story: You see we can’t live inland with the rest of the people. We go and live outside on the beach. That’s how we survive and what we can do. People come here for a week; they can’t survive like we survive. Because they have to have breakfast, lunch, and everything in between. But we’re used to eating different hours; different eating habits. It doesn’t matter if you’re not getting much fish, but there’s always fish to eat. I can’t go and stand on the road and beg for money, I can’t. I’ve never done that in my life. I’d rather look for something to eat on the rocks. There’s a lot of things you can eat, mussels, anything from the rocks – crabs, anything you can chow, you can survive. There’s always something to catch and eat, and maybe make a little bit of money for yourself to survive and buy maybe bread and things to eat for the possie, like onions, potatoes and oil, and get your gas bottle filled. We smaak our curry spices. You take a fish, put your curry spices, fry it in deep oil and eat it with bread and butter. Or even pap, even mielie meal (Laughter). That’s how we survive. You don’t steal from anybody and no one steals from people here. All our families live together. Read more >>

Grant’s story: Where have all the bait fish gone?

This artwork and accompanying story illustrate the knowledge of small-scale fishers, including on the impacts of climate change and pollution, which serve to understanding the inter-dependence of small-scale fishers economic, social and cultural rights.

Casey Pratt, photograph, 2021

Grant’s story: Well, we move to the Bluff I think I was 5 years old, and from then we started going down to the beach and swimming, so it has been a long time and there are lots of memories. There were lots of things we use to do, fish and sorts of things. My father taught me to fish, I think I was about 6 years old. I would classify myself as a recreational fisherman. I have fished off the beach, I have fished off a paddle ski and I have fished off a ski-boat and I have caught lots of fish off all three. But I think the best one I had was fishing on a paddle-ski and I caught a 27kg barracuda and it towed me for quite a bit. It towed me between Brighton and Anstey’s so. I landed it, it took me close to ¾ of an hour, and I have just one photo. Read more >>